I. We say kids are resilient. What we mean is: They’ll survive whatever you do to them—and we won’t have to clean up the mess.

I was born in San Francisco in 1972, right off Haight Street. My dad was schizophrenic—violent, unstable, and in and out of jobs, booze, and drugs. My mom was loving but too young, too broke, and completely overwhelmed.

The apartment was run-down, like most of the places we lived back then. We were poor. But there were moments of real childhood there. My brother and I ran around barefoot, totally unsupervised, crawling under the building, playing with neighborhood kids, running up and down the stairs to our friends’ apartments. My mom would take us to Golden Gate Park, and those days were fun—playing, being outside, just being with her. When it was just us and her, away from the house, things felt okay.

But inside the apartment, everything felt unsteady. Not because of the building—but because of my dad. He would break things, scream, argue with my mom, say things that made no sense, and snap without warning. You never knew when it was going to happen—but you always knew it would.

It wasn’t all bad. But it was weird. And it was scary. And we never felt totally safe.

Then one day, when I was four, my father showed up at the door with a wheelbarrow. Inside was an axe.

There was no warning. No lead-up. He just came through the door and went after my mother. I remember her on the ground, screaming, trying to hold the axe back as he pushed it toward her face. Not her neck—her face. He was trying to kill her.

The next thing I remember is her hand—bleeding. He had nearly severed one of her fingers. There had been a struggle at the window, and he’d slammed it shut on her hand. She was yelling at us to get out. Just over and over: “Get out, get out, get out!”

I know it was daytime, but in my memory, it’s dark. I can’t see much. Just blood, noise, panic. I think the neighbors came and pulled us out. The police were called. And I remember being picked up by Amy and Roy. That’s it. Everything else is gone. It was visceral. And even now, just thinking about it makes my chest tighten.

They took us in, and suddenly, we were living a different kind of life.

We went to the beach. Took martial arts classes. Went to Disneyland. Had birthday parties that felt like magic. Everything about those two years felt safe, warm, and normal in a way I didn’t fully understand until it was gone.

I remember asking if we could call them Mom and Dad. It wasn’t some big emotional moment—we just said it one day, and it stuck. Amy was warm. She gave hugs like they were automatic. She didn’t flinch when you reached for her. She didn’t act like your presence was a burden. There was no tension. No fear. Just this quiet safety that wrapped around you like a blanket.

It felt natural. It felt safe. And that was rare enough to feel like a miracle.

II. The Theft of Peace

It was supposed to be a visit.

That’s what they told Amy and Roy. My birth mom said she just wanted to see us. Nothing more. So Amy agreed to take us to Iowa.

But it wasn’t a visit. It was a setup.

I remember sitting with this woman who was telling me she was my “real mom.” I kept saying, “No—I need my real mom.” I meant Amy. I meant the woman who hugged me without hesitation, who made sure we had birthday cake, who took us to the beach. That was my mom. The one I chose. The one who made me feel safe.

The adults around us laughed when I said it. Laughed.

That moment shattered something I hadn’t even realized could break. I didn’t understand what was happening. I didn’t know why Amy wasn’t stopping it. I just knew that I was being pulled away from the only home that had ever felt like one. And I knew, even then, that I would never see her again.

That night, my brother and I shared a bed. I turned to him and asked, “Do you think Mom is coming to get us?”

He said, “No. She’s not. She’s not our real mom.”

He remembered. I didn’t.

That was the night I stopped trusting adults.

My mom had remarried. Her new husband’s name was Whitey. He’d done twenty years in San Quentin for bank robbery. She met him in a halfway house. By the time we got there, she’d had a new baby—my younger sister Maggie.

Whitey wasn’t physically abusive. He wasn’t kind either. He was a militant disciplinarian, or totally absent. There was no warmth. No attention. No guidance. He didn’t teach me anything. Didn’t ask how I was. Didn’t show up for anything.

There was one time—my 10th birthday—when he decided to do something “fatherly.” He said he was taking me to a movie. That sounded good. I remember being hopeful, maybe even a little excited.

The movie was An American Werewolf in London. I was ten.

Before we went in, he led me around the corner into an alley. No explanation. No warning. He lit up a joint and handed it to me. Just handed it to me—like we were two guys hanging out, like I was supposed to be cool with it. So I smoked it. What else was I supposed to do?

I sat in that theater gripping the armrests, absolutely terrified. The movie itself was brutal, and the weed only made it worse. I was high, paranoid, scared out of my mind. I thought I was going to piss myself. I didn’t. But I could’ve.

When it was over, he looked at me and said, “Pretty fun, right?”

That was his idea of a father-son moment.

Turns out, not being hit doesn’t mean you’re safe. Sometimes the damage comes with a smile.

The house was strange. Chaotic. My mom, Whitey, and her sister all slept in the same bed. It was obvious what was going on. We were kids—we knew. There were no boundaries. No privacy. No safe space. Just a kind of constant, low-level dysfunction that you had to get used to or be consumed by.

There was food. But there was no dignity. I was wearing hand-me-downs I was embarrassed by. I didn’t have proper shoes, so I couldn’t even participate in gym. I felt humiliated.

So at nine, I got a paper route.

I’d wake up at 4:30 in the morning in the middle of an Iowa winter and deliver newspapers—just so I wouldn’t feel like a piece of shit. Just so I could afford a decent pair of jeans. Just so I could buy a little dignity for myself.

At first, it worked. I felt like I had control over something.

Then the adults started stealing my money.

Month after month, I’d go to pay the paper company and come up short. I didn’t know why. I didn’t know who was taking it. I just knew that the money was gone, and I was the one being held responsible.

I remember calling them, trying to explain. Trying to make sense of it. I was furious. I wanted to cry. I felt ashamed and betrayed. I didn’t know who to blame, because no one would admit to anything. And I was a kid. No one cared what I thought.

Later, my brother told me the truth—they’d been stealing the money.

So I picked up other odd jobs. Mowed lawns. Did whatever I could to make up the difference. Eventually, I quit. I wasn’t going to keep working for free.

That was the first time I understood how the system really works:

You do the labor.

They take the profits.

And you get blamed when the numbers don’t add up.

III. The Collapse

Then Whitey robbed a bank.

It wasn’t subtle. It wasn’t slick. He just walked into a downtown branch, jumped the counter, shoved a couple of clerks out of the way, grabbed about ten thousand dollars, and walked out. That was it. It was on the news. I remember seeing it on TV before he even made it home.

That was the last straw for my mom. He took off for Texas to let the heat die down, and when he came back, the cops were ready. A SWAT team staked out our house.

They didn’t explain anything. No one said why they were there or what we were supposed to do. That’s how things always were. No context, no support—just orders.

My bedroom was in the attic, the very top floor of the house. That’s where they put the sniper. The window was already broken—I’d broken it myself weeks before. The officer didn’t say much. He just came in, poked his rifle through the broken frame, and set up. We were told to stay out of the way. That was it. No evacuation. No safety plan. Just stay out of the sniper’s line of fire in your own home.

I remember being downstairs in the living room, looking out through a window. Whitey’s car came around the corner, and suddenly the street exploded. Police swarmed the car and dragged him out. I just watched.

Later, I was in court when he fired his lawyer mid-hearing. The guy had brought up the bank robbery, even though the charges were only for illegal firearms possession. Whitey stood up, dismissed him, and started representing himself. Whatever he said worked—he got six months. They couldn’t prove the robbery. No positive ID. Bad footage. He walked on that charge.

After he got out, he took off again—this time with the car. He left my mom and the rest of us behind with nothing. No vehicle. No way to get around. No way to carry groceries across town. Every week, my mom and I would walk for miles to get food and haul it back in bags. It was exhausting. Embarrassing. Humiliating. Everyone in that small town knew. Everyone stared. No one helped.

The utilities were shut off. No heat. No power. No water.

My mom couldn’t find work. She wasn’t legally divorced, which created more barriers. She started drinking. And not just socially—she drank to numb everything. To disappear.

I started drinking too. At eleven.

Older kids brought me into their orbit. I started partying, stealing alcohol, doing whatever I had to do to fit in. I was charming, and I was young, and I was attractive in the kind of way that broken people are drawn to. Girls gave me money. They fed me. I didn’t really understand what any of it meant. I just knew it worked.

Then one night, I woke up choking on my own vomit.

I was flat on the floor. I couldn’t breathe. I rolled over and it all came out. Even at that age, I understood—I could have died. I knew what aspiration was. I knew how thin the line was between waking up and not.

And there was nobody there. No one noticed. No one helped.

Just me. Alone. In a cold, empty house. No electricity. No plumbing. Just silence.

I looked around and knew none of the teenagers I’d been drinking with were going to do a damn thing for me. I had no friends. No family. No backup. No plan. Just a broken body, a broken system, and the realization that this is how it is now.

That was the moment I stopped looking to adults for anything.

I stopped expecting anyone to tell me what was right or wrong. I stopped believing that people were there for each other. I stopped imagining there was some grown-up coming to step in.

I didn’t expect to live long. I didn’t see adulthood as something real. I didn’t see the future. I saw now—and I figured if no one gave a shit, I might as well enjoy myself while I could.

Consequences didn’t matter anymore.

Because when no one cares if you live or die, the rules stop applying.

Here is Section Four—the final act. This is where everything you lived through turns into the fire behind GreedBane. The pain, the abandonment, the rot in every institution—they all lead here. This section is structured to land like a hammer while staying entirely in your voice, honoring every piece of this truth.

IV. The System Was Working as Designed

This isn’t just a personal story.

It’s not just about my dad and his schizophrenia.

Not just about my mom being overwhelmed.

Not just about a broken window, or a paper route, or a movie I never should have seen.

It’s about a country that let it all happen—and kept on moving.

I wasn’t just failed by a parent. I was failed by every system that claimed it existed to protect me.

School didn’t help. I had ADHD and dyslexia. I needed glasses and didn’t have them. I couldn’t see the board. Couldn’t keep up. So instead of support, they pulled me out of class and sent me to what everyone called the “retard room.” I remember sitting there, humiliated. Not understanding why I was being punished for being poor. For being confused. For being a kid who needed help and didn’t know how to ask for it.

No one ever checked in. No counselor. No advocate. No CPS.

There was no plan. No rescue.

My mom applied for welfare. I remember going with her. It was humiliating. The system wasn’t built to help her—it was built to humiliate her into giving up. It was a maze of forms, denials, low-wage job offers, and judgment. They offered her a job as a waitress making a dollar and change an hour. She had a college degree. Three kids. No car. No childcare. What exactly was she supposed to do?

We got food stamps. That was something. But it wasn’t enough. Nothing else worked. Nothing else was meant to work.

Welfare in America isn’t safety. It’s punishment. It’s paperwork wrapped in shame. It’s a lesson: don’t ask for help. No one is coming.

The system never failed.

It did exactly what it was built to do.

To extract.

To punish.

To discard.

And it’s only gotten worse.

Now they cut more. Demand more. Blame harder. Politicians talk about “bootstraps” while gutting every rung of the ladder. They strip schools. Starve social programs. Criminalize poverty. Then turn around and call it freedom.

They don’t want to fix the system. Because for them, it’s not broken. It’s working exactly as designed.

I didn’t overcome my childhood.

I outlasted it.

And that’s why I fight.

Because there are still kids choking in the dark while billionaires fly to space. Still families walking miles with groceries while lobbyists dine with lawmakers. Still mothers being told they’re lazy, while corporations pay nothing and steal everything.

That’s why I built GreedBane.

To expose the machinery behind the misery.

To name the villains.

To fight for the people no one else is watching.

To burn down the narrative that says this suffering is normal.

Because this wasn’t resilience.

This was survival.

And if I have anything to say about it—

the next kid won’t have to survive alone.

In Solidarity,

Greedbane

05/17/2025

If my story moved you—don’t just scroll past it.

Subscribe. Share it. Talk about it.

Because silence is what keeps systems like this alive.

And if you’re ready to go deeper—become a paid subscriber.

You’re not just supporting my work.

You’re helping me build a platform that exposes the rot and fights for the kids no one else is watching.

Let’s burn their narrative to the ground—together.

“No one was coming to save me. So I became the man I needed—and built the family I never had.”

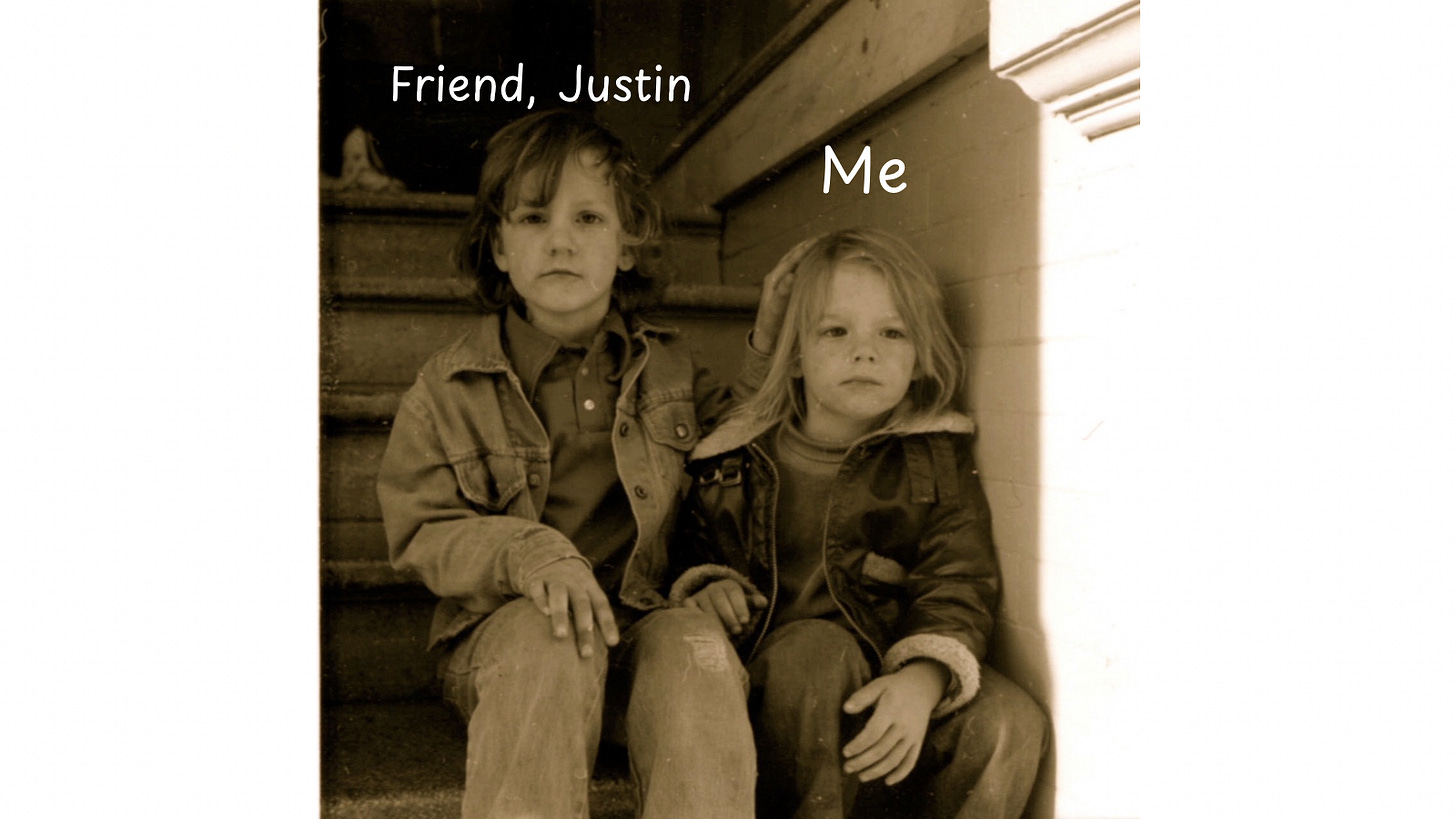

“This is what surviving the system looks like. Still standing. Still together.”

“I never had birthday parties. My kids get castles.”

Such a powerful narration. Thank you for the enlightening reveals. I am sorry we failed you. But I am encouraged that you made it through hell and are now a force for good. Let us not fail more children.

The trauma never truly heals and the scars remain visible, no matter what you do. The system truly is made to break us, and it desperately needs to be completely replaced! Not reformed. Completely replaced!!